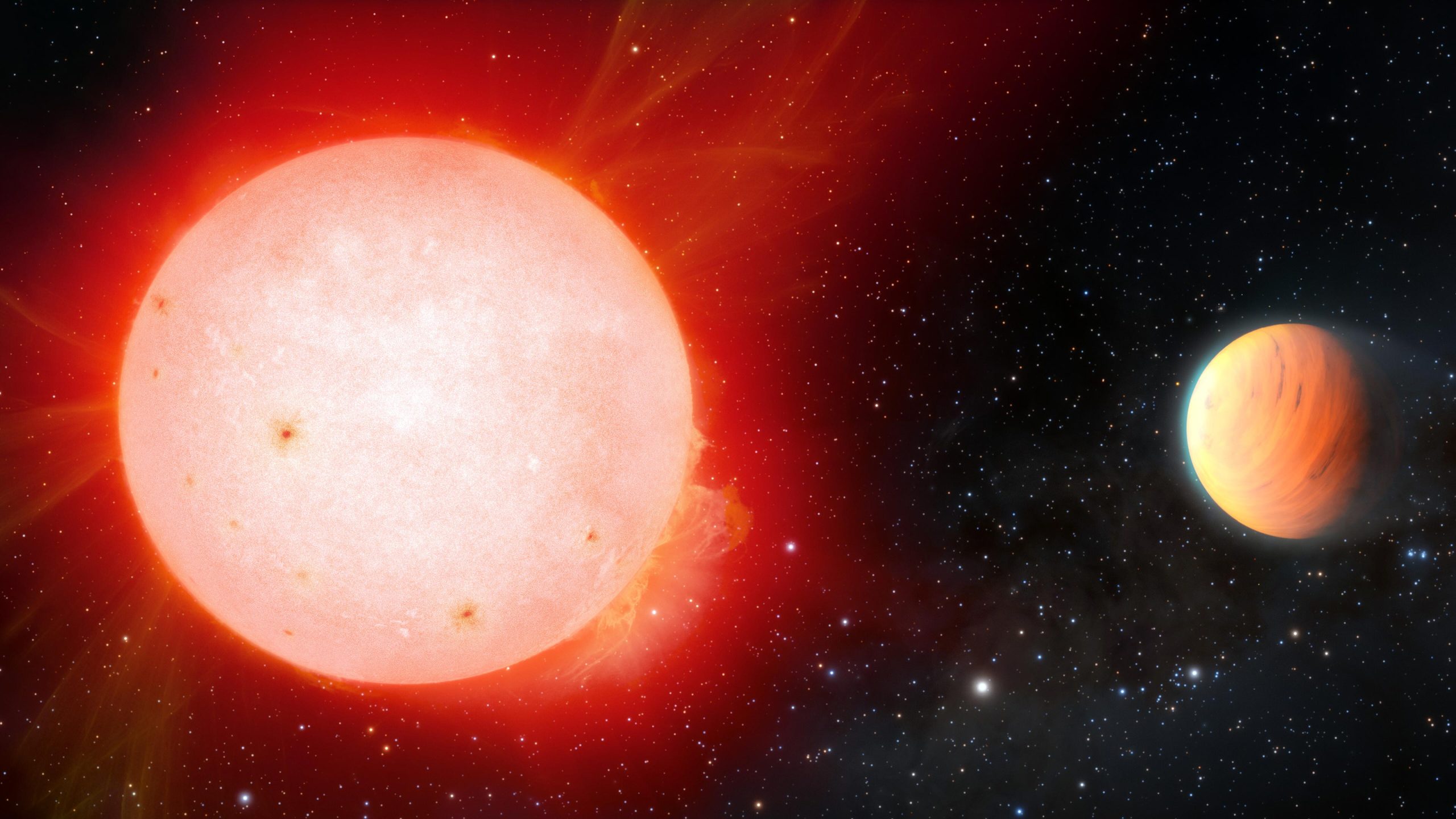

Impresión artística de un planeta gigante gaseoso ultrasuave que orbita una estrella enana roja. Un exoplaneta gigante gaseoso [right] con la densidad de un malvavisco se detectó en órbita alrededor de una estrella enana roja fría [left] por el instrumento de velocidad radial NEID financiado por la NASA en el telescopio WIYN de 3,5 metros en el Observatorio Nacional Kitt Peak, un programa del NOIRLab de la NSF. El planeta, llamado TOI-3757 b, es el planeta gigante gaseoso más suave jamás descubierto alrededor de este tipo de estrella. Crédito: NOIRLab/NSF/AURA/J. da Silva / Motor espacial / M. Zamani

El telescopio del Observatorio Nacional Kitt Peak ayuda a determinar esto[{» attribute=»»>Jupiter-like Planet is the lowest-density gas giant ever detected around a red dwarf.

A gas giant exoplanet with the density of a marshmallow has been detected in orbit around a cool red dwarf star. A suite of astronomical instruments was used to make the observations, including the NASA-funded NEID radial-velocity instrument on the WIYN 3.5-meter Telescope at Kitt Peak National Observatory, a Program of NSF’s NOIRLab. Named TOI-3757 b, the exoplanet is the fluffiest gas giant planet ever discovered around this type of star.

Using the WIYN 3.5-meter Telescope at Kitt Peak National Observatory in Arizona, astronomers have observed an unusual Jupiter-like planet in orbit around a cool red dwarf star. Located in the constellation of Auriga the Charioteer around 580 light-years from Earth, this planet, identified as TOI-3757 b, is the lowest-density planet ever detected around a red dwarf star and is estimated to have an average density akin to that of a marshmallow.

Red dwarf stars are the smallest and dimmest members of so-called main-sequence stars — stars that convert hydrogen into helium in their cores at a steady rate. Although they are “cool” compared to stars like our Sun, red dwarf stars can be extremely active and erupt with powerful flares. This can strip orbiting planets of their atmospheres, making this star system a seemingly inhospitable location to form such a gossamer planet.

«Se ha pensado tradicionalmente que los planetas gigantes alrededor de estrellas enanas rojas son difíciles de formar», dice Shubham Kanodia, investigador del Laboratorio de Tierra y Planetas de la Institución Carnegie para la Ciencia y primer autor de un artículo publicado en El día astronómicol “Hasta ahora, esto solo se ha observado con pequeñas muestras de encuestas Doppler, que generalmente han encontrado planetas gigantes más alejados de estas estrellas enanas rojas. Hasta ahora no hemos tenido una muestra lo suficientemente grande de planetas para encontrar planetas gaseosos sólidamente cercanos».

Todavía hay misterios sin explicar en torno a TOI-3757 b, el más grande es cómo se puede formar un planeta gigante gaseoso alrededor de una estrella enana roja, y especialmente un planeta de baja densidad. El equipo de Kanodia, sin embargo, cree que puede tener una solución a ese misterio.

Desde el suelo del Observatorio Nacional Kitt Peak (KPNO), un programa de NOIRLab de NSF, el telescopio de 3,5 metros de Wisconsin-Indiana-Yale-NOIRLab (WIYN) aparentemente observa la Vía Láctea a medida que emerge del horizonte. Un resplandor rojizo, un fenómeno natural, también tiñe el horizonte. KPNO está ubicado en el desierto de Arizona-Sonoran en la nación Tohono O’odham y esta vista clara de parte del plano galáctico de la Vía Láctea muestra las condiciones favorables en este entorno necesarias para observar objetos celestes tenues. Estas condiciones, que incluyen bajos niveles de contaminación lumínica, un cielo más oscuro que una magnitud 20 y condiciones atmosféricas secas, han permitido a los investigadores del Consorcio WIYN realizar observaciones de galaxias, nebulosas y exoplanetas, así como muchos otros objetivos astronómicos utilizando el WIYN. telescopio El telescopio de 3,5 metros y su hermano el telescopio WIYN de 0,9 metros. Crédito: KPNO/NOIRLab/NSF/AURA/R. chispas

Proponen que la densidad extremadamente baja de TOI-3757 b podría ser el resultado de dos factores. El primero se refiere al núcleo rocoso del planeta; Se cree que los gigantes gaseosos comenzaron como enormes núcleos de roca de unas diez veces la masa de la Tierra, momento en el que rápidamente atraen grandes cantidades de gas cercano para formar los gigantes gaseosos que vemos hoy. La estrella TOI-3757b tiene una menor abundancia de elementos pesados que otras enanas M con gigantes gaseosos, y esto puede haber llevado a una formación más lenta del núcleo rocoso, lo que retrasó el inicio de la acumulación de gas y, por lo tanto, afectó la densidad general del planeta.

El segundo factor podría ser la órbita del planeta, que se cree que es ligeramente elíptica. Hay momentos en los que se acerca más a su estrella que en otros momentos, provocando un exceso de calor significativo que puede hacer que la atmósfera del planeta se hinche.

Satélite de sondeo de exoplanetas en tránsito de la NASA ([{» attribute=»»>TESS) initially spotted the planet. Kanodia’s team then made follow-up observations using ground-based instruments, including NEID and NESSI (NN-EXPLORE Exoplanet Stellar Speckle Imager), both housed at the WIYN 3.5-meter Telescope; the Habitable-zone Planet Finder (HPF) on the Hobby-Eberly Telescope; and the Red Buttes Observatory (RBO) in Wyoming.

TESS surveyed the crossing of this planet TOI-3757 b in front of its star, which allowed astronomers to calculate the planet’s diameter to be about 150,000 kilometers (100,000 miles) or about just slightly larger than that of Jupiter. The planet finishes one complete orbit around its host star in just 3.5 days, 25 times less than the closest planet in our Solar System — Mercury — which takes about 88 days to do so.

The astronomers then used NEID and HPF to measure the star’s apparent motion along the line of sight, also known as its radial velocity. These measurements provided the planet’s mass, which was calculated to be about one-quarter that of Jupiter, or about 85 times the mass of the Earth. Knowing the size and the mass allowed Kanodia’s team to calculate TOI-3757 b’s average density as being 0.27 grams per cubic centimeter (about 17 grams per cubic feet), which would make it less than half the density of Saturn (the lowest-density planet in the Solar System), about one quarter the density of water (meaning it would float if placed in a giant bathtub filled with water), or in fact, similar in density to a marshmallow.

“Potential future observations of the atmosphere of this planet using NASA’s new James Webb Space Telescope could help shed light on its puffy nature,” says Jessica Libby-Roberts, a postdoctoral researcher at Pennsylvania State University and the second author on this paper.

“Finding more such systems with giant planets — which were once theorized to be extremely rare around red dwarfs — is part of our goal to understand how planets form,” says Kanodia.

The discovery highlights the importance of NEID in its ability to confirm some of the candidate exoplanets currently being discovered by NASA’s TESS mission, providing important targets for the new James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) to follow up on and begin characterizing their atmospheres. This will in turn inform astronomers what the planets are made of and how they formed and, for potentially habitable rocky worlds, whether they might be able to support life.

Reference: “TOI-3757 b: A low-density gas giant orbiting a solar-metallicity M dwarf” by Shubham Kanodia, Jessica Libby-Roberts, Caleb I. Cañas, Joe P. Ninan, Suvrath Mahadevan, Gudmundur Stefansson, Andrea S. J. Lin, Sinclaire Jones, Andrew Monson, Brock A. Parker, Henry A. Kobulnicky, Tera N. Swaby, Luke Powers, Corey Beard, Chad F. Bender, Cullen H. Blake, William D. Cochran, Jiayin Dong, Scott A. Diddams, Connor Fredrick, Arvind F. Gupta, Samuel Halverson, Fred Hearty, Sarah E. Logsdon, Andrew J. Metcalf, Michael W. McElwain, Caroline Morley, Jayadev Rajagopal, Lawrence W. Ramsey, Paul Robertson, Arpita Roy, Christian Schwab, Ryan C. Terrien, John Wisniewski and Jason T. Wright, 5 August 2022, The Astronomical Journal.

DOI: 10.3847/1538-3881/ac7c20

«Maven de internet exasperantemente humilde. Comunicadora. Fanático dedicado al tocino.»

También te puede interesar

-

Dormir bien el fin de semana puede reducir en una quinta parte el riesgo de sufrir enfermedades cardíacas: estudio | Cardiopatía

-

Una nueva investigación sobre la falla megathrust indica que el próximo gran terremoto puede ser inminente

-

Caso de Mpox reportado en la cárcel del condado de Las Vegas

-

SpaceX lanzará 21 satélites Starlink en el cohete Falcon 9 desde Cabo Cañaveral – Spaceflight Now

-

SpaceX restablece el lanzamiento pospuesto de Polaris Dawn, una misión espacial comercial récord